|

McCloud River Railroad McCloud River Lumber Company Panama-Pacific Exposition |

|

|

|

|

Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

|

Introduction

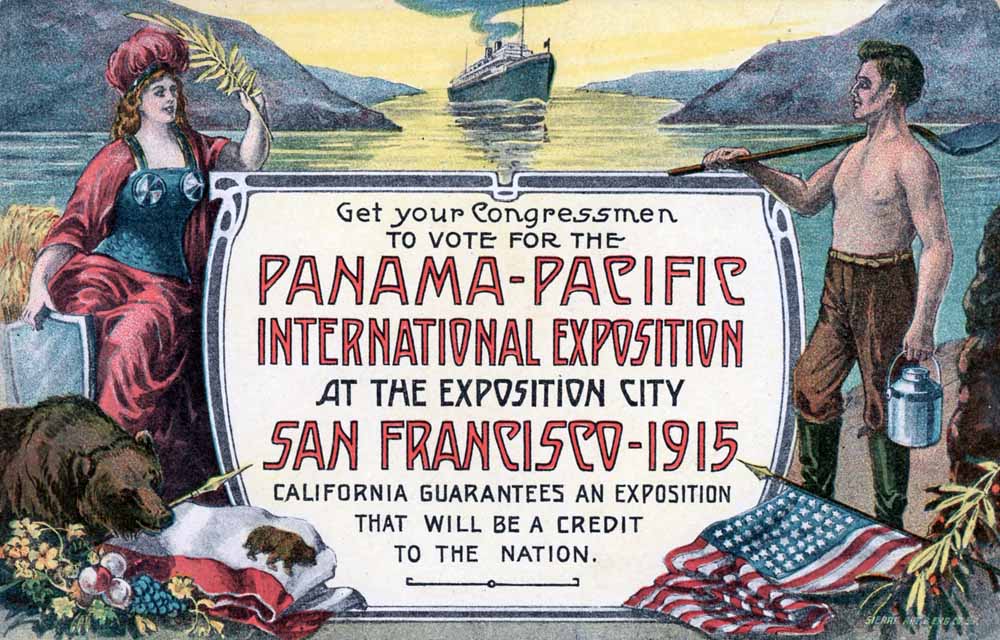

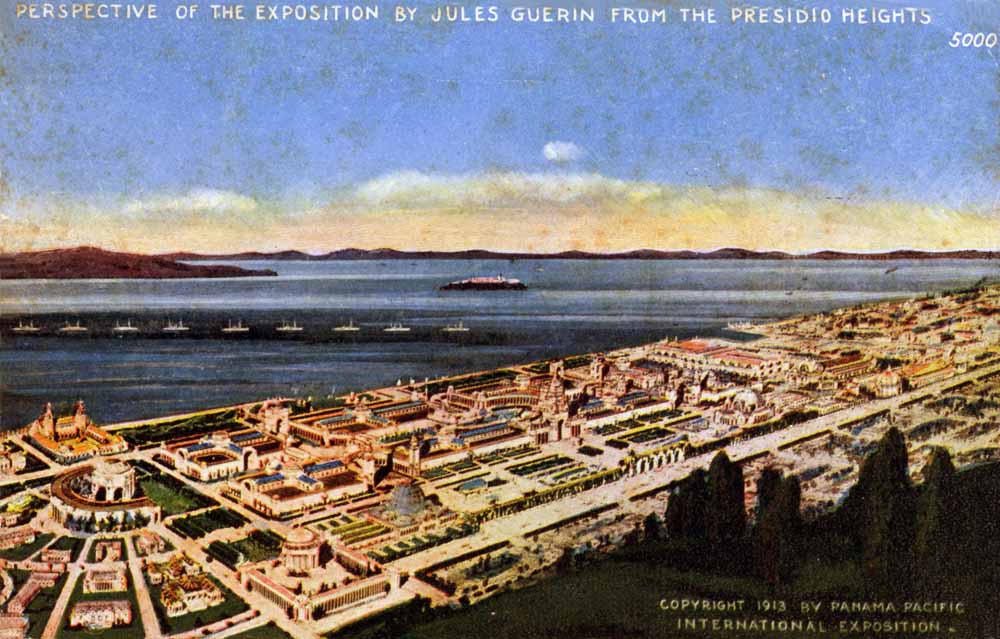

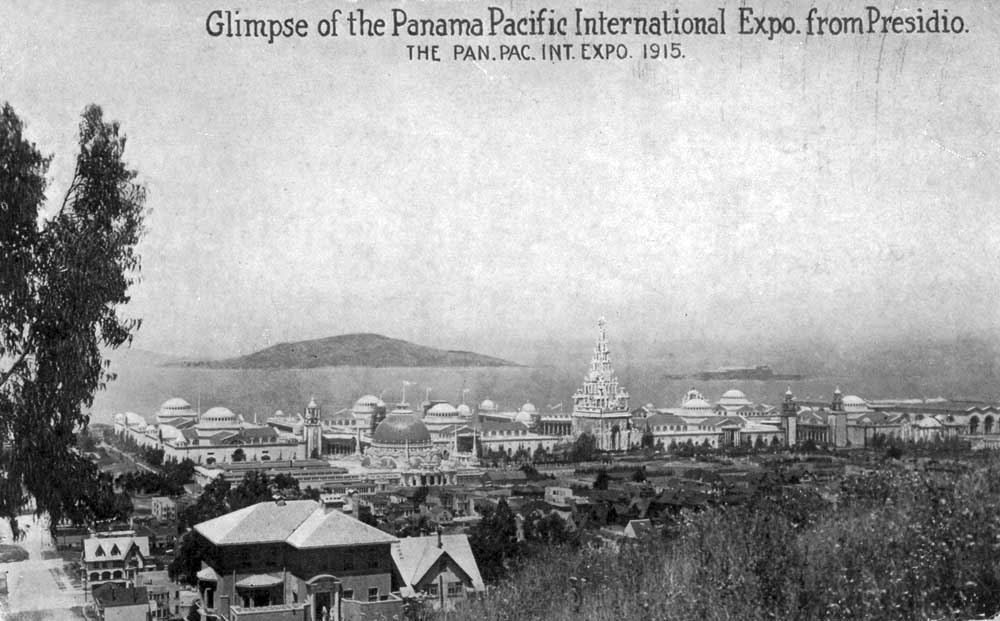

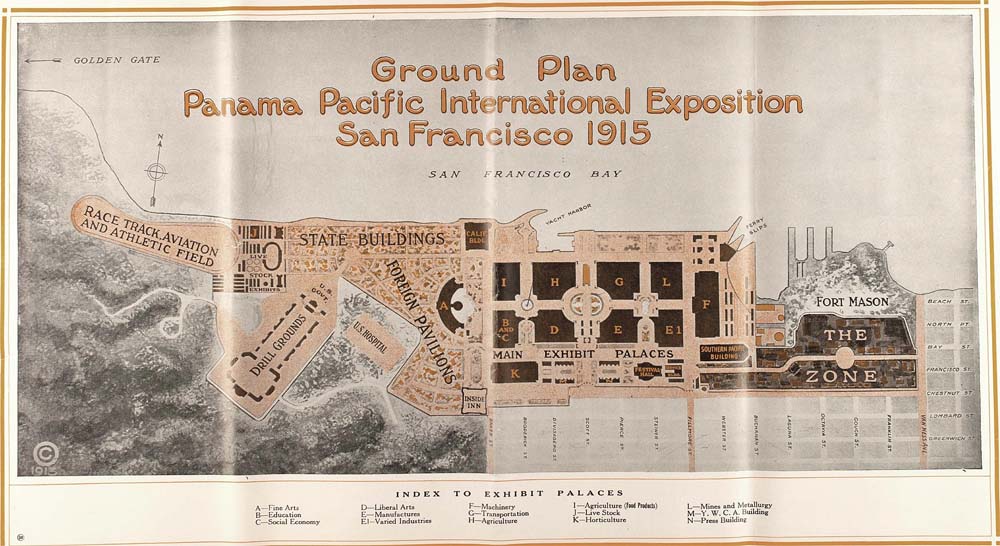

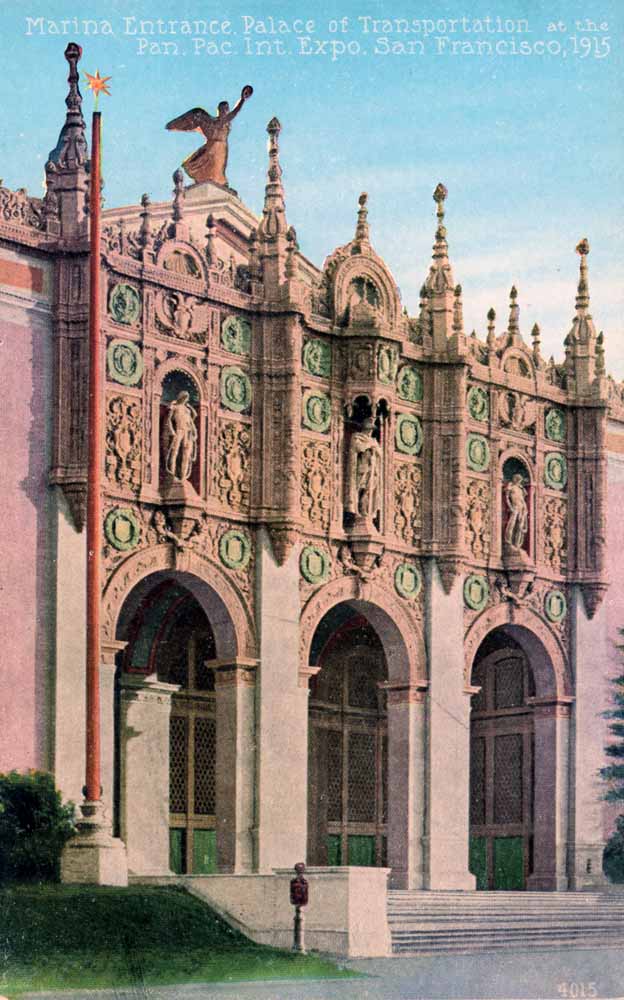

A San Francisco based merchant association led by local business tycoon Rueben Hale first proposed the idea of hosting a World's Fair type event in the city in connection with the opening of the Panama Canal in 1904. The canal had only been under construction for about two years by this point and was a long ways from completion, and that plus the catastrophic San Francisco earthquake in 1906 deferred planning. The backers forged ahead, however, and incorporated the Panama Pacific Exposition Company in December 1906. Reconstructing the city consumed most of the backer's attentions and resources over the next several years, but by 1910 they were ready to start planning in earnest. San Francisco then had to fend off several other cities that wanted to host the exposition, including Washington D.C., Boston, New Orleans, and San Diego. San Francisco successfully lobbied its case, and defeated the other parties through a combination of a massive public relations campaign coupled with a promise not to accept any Federal funding. President Taft signed a resolution designating San Franscisco as the home of the Panama Pacific Exposition on 5 February 1911, though the official designation did not stop a very determined San Diego from hosting its own concurrent Panama California Exposition. Planning the exposition began in earnest. The company eventually settled on a 636-acre site along two and a half miles of bayfront property on the northern edge of the city, which came with a lot of challenges as it required them to buy over 75 city blocks, demolish over 200 existing structures, fill in both some low lying marsh land and parts of the bay, and negotiate with the military to build on some of their land on both the Presidio and Fort Mason. The architects and planners established from the start that the exposition buildings and grounds would be temporary. Eight large exhibition palaces, each devoted to a major economic sector, formed the heart of the exposition, surrounded by hundreds of smaller pavilions and buildings along with acres of gardens and other landscaping. Most nations and all states had their own pavilions or other structures, and several large international sporting events happened on the grounds throughout the exposition. It has often been said that a person could have spent every minute the exposition was open between 20 February and 4 December 1915 on the grounds and still not have seen everything on display. The organizers set several themes for the exposition, with heavy emphasis on connecting east and west and celebrations of human advancements and achievements. The exposition wanted representation of every major industry in the nation, especially California. Both the McCloud River Lumber Company and McCloud River Railroad Company participated in the exposition as part of the timber and transportation industries. |

|

|

|

|

An overview of the exposition as seen from the Presidio heights. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

Another view from the Presidio. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

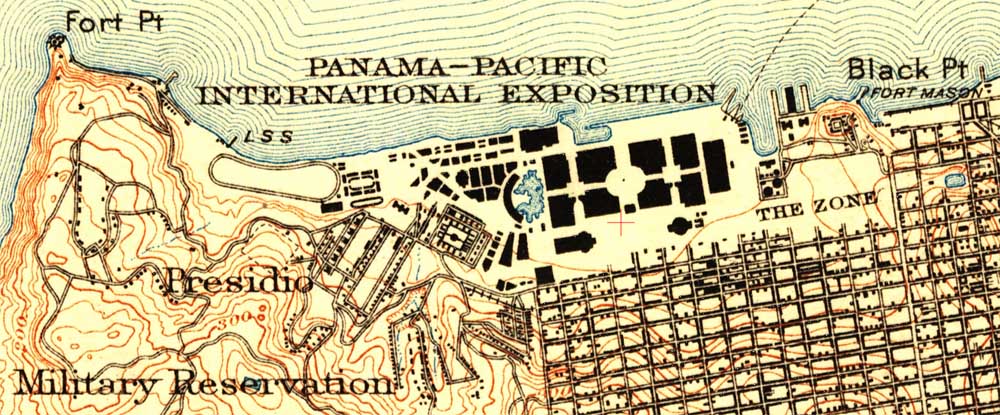

A map of the Panama-Pacific exposition grounds.

|

|

|

The grounds on a period topographical map.

|

|

|

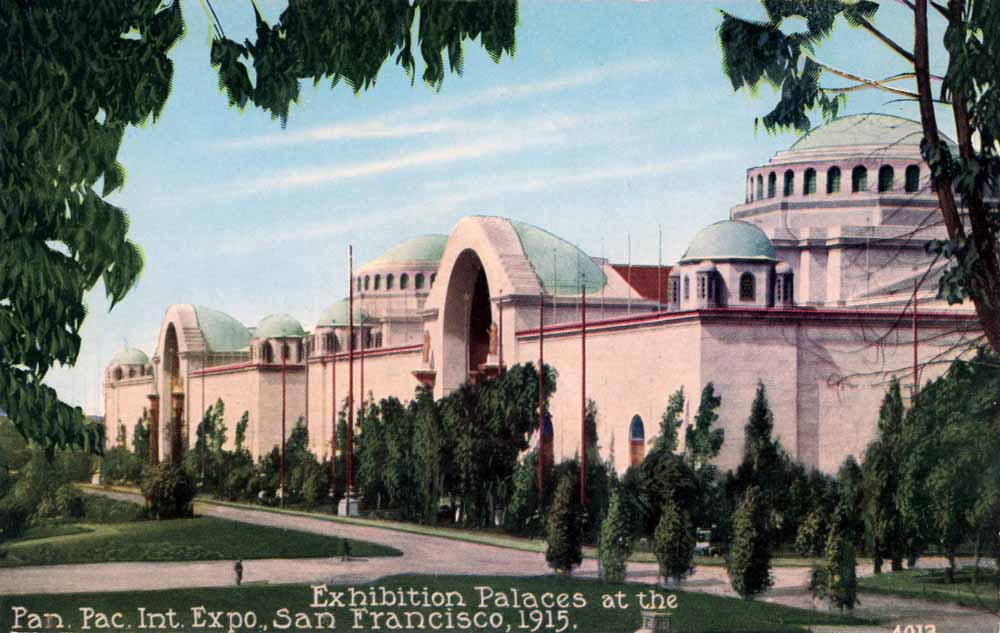

A postcard view of the exposition palaces. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

The Southern Pacific exposition hall. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

The Palace of Fine Arts, which is the only major building from the exposition that still survives today. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

A promotional postcard for the exposition. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

The California Counties building that contained exhibits prepared by each county. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

|

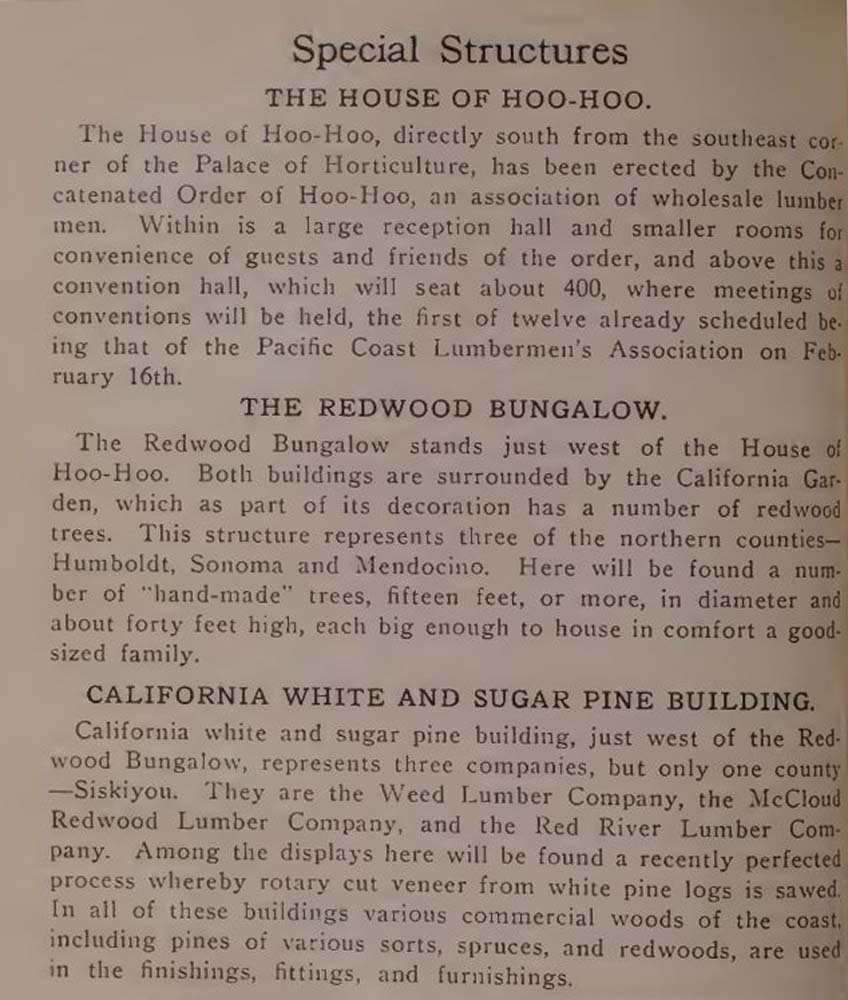

Forestry and the California White & Sugar Pine Industries Building

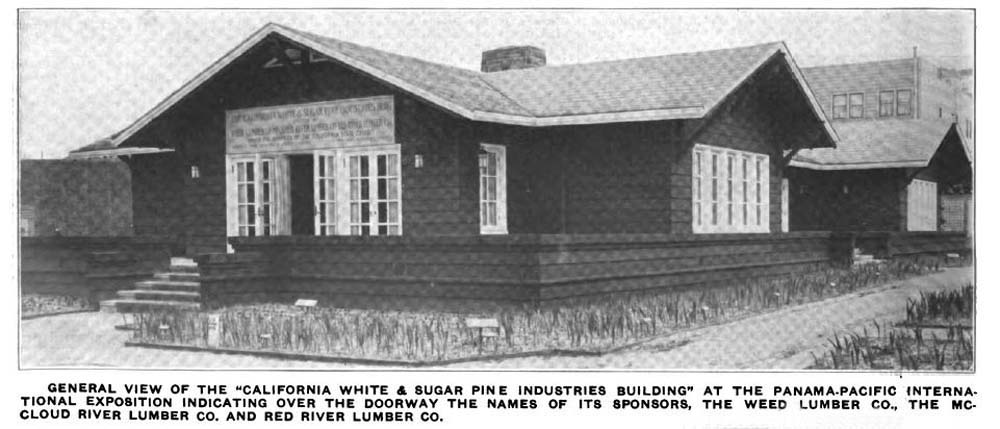

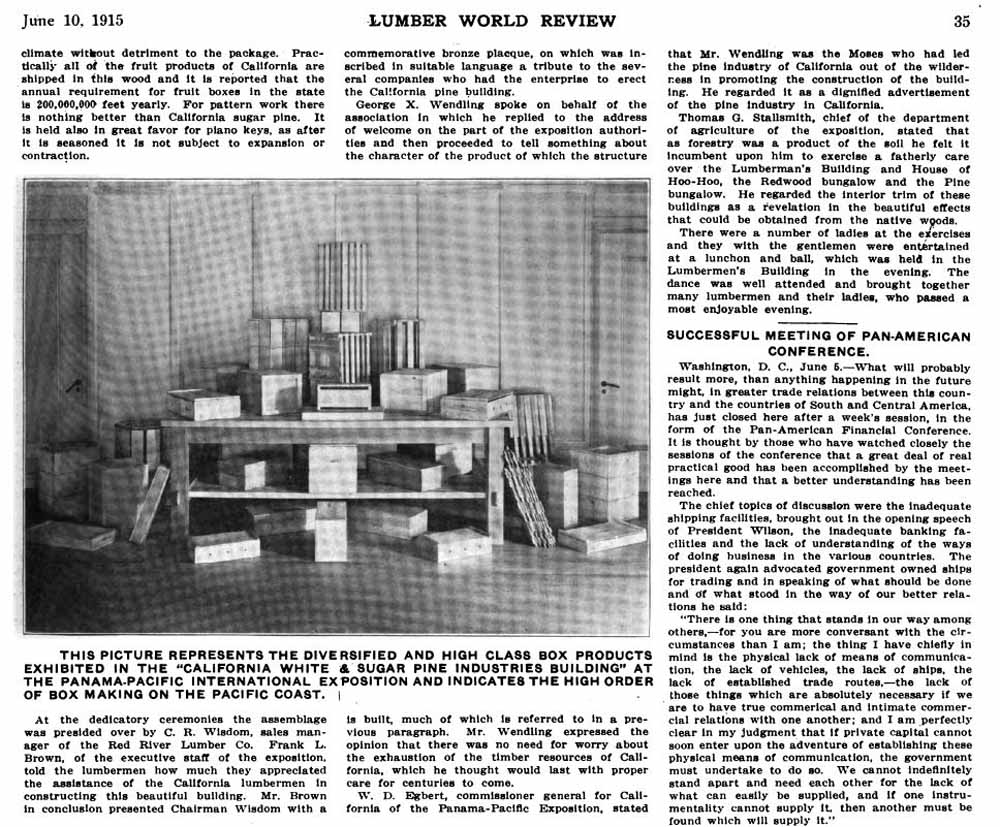

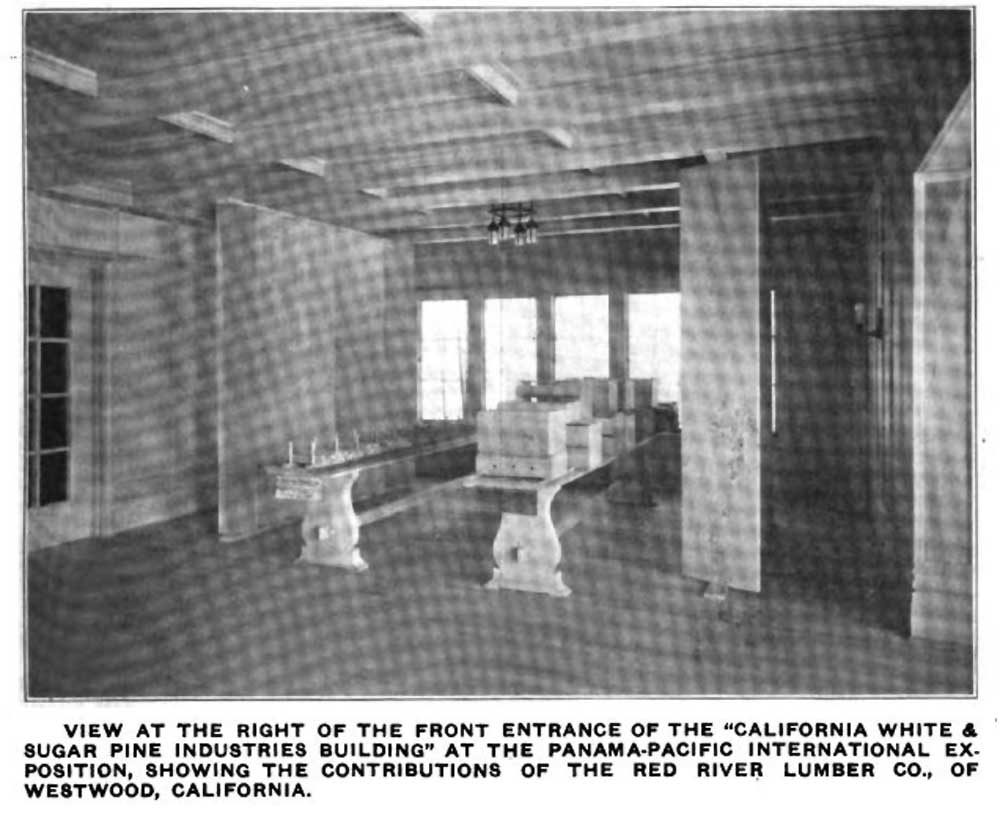

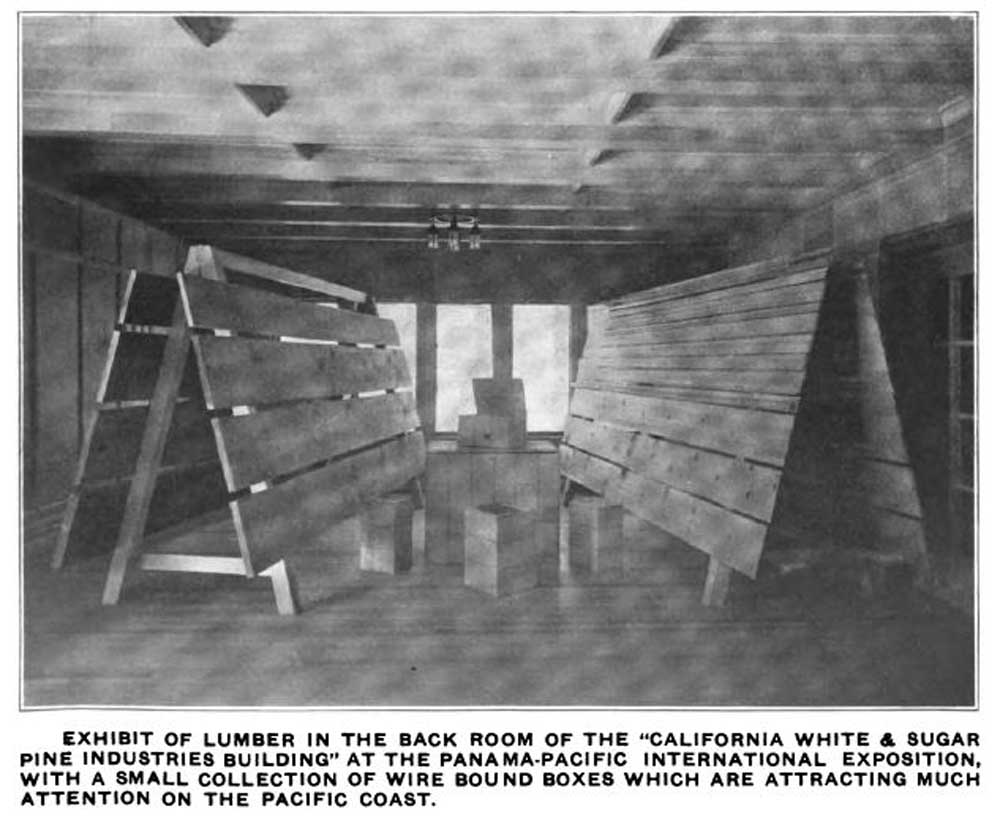

The lumber industry played a huge role in reconstructing San Francisco after the earthquake, and for that it would receive special recognition in the Exposition. The Forestry exhibit was centered around three buildings. The International Order of Hoo Hoo, the lumber industry's own fraternal organization, constructed the most impressive of the three buildings that would serve as a meeting point and lounge for industry professionals but was only open to the public for a few days during the exposition's run. The building was an impressive one, complete with tree trunks set up like a forest around the building. The House of Hoo Hoo was one of the few buildings that survived the exposition, as a businessman bought the structure and moved it to Cupertino where is served as a roadhouse and some other similar establishments until it burned in 1926. The lumber industry itself sponsored the other two buildings, one by the redwood industry operating along the coast and the other- the California White & Sugar Pine Industries Building- jointly by the Weed, Red River, and McCloud River lumber companies. The buildings showcased the products and operations of the industries in the regions. The three pine companies jointly built the White & Sugar Pine house using the products of their sawmills save for metal fastenings and a lava rock fireplace constructed from rock quarried in the region. |

|

|

|

|

|

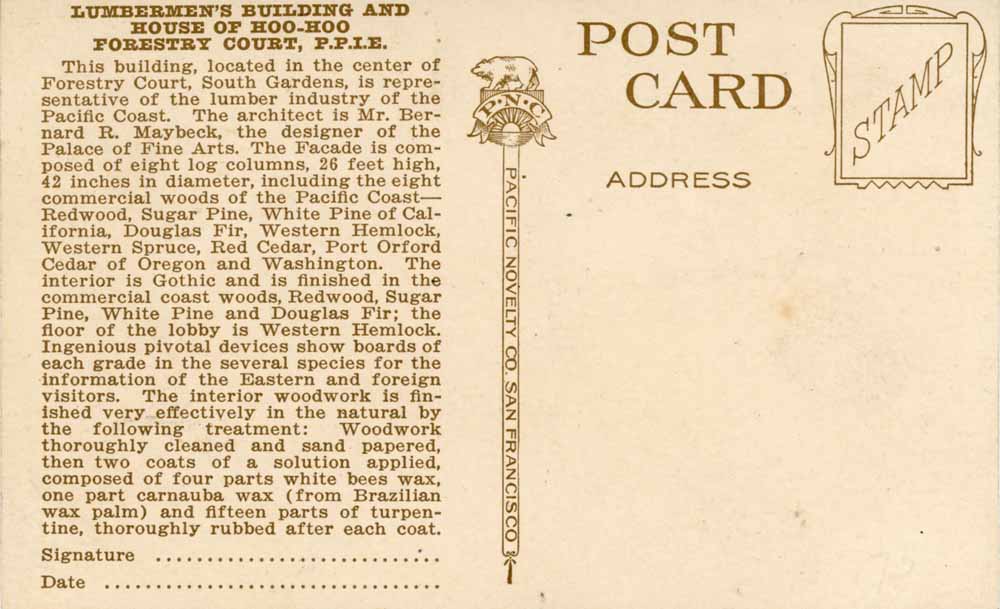

Postcard featuring the Lumberman's Building/House of Hoo Hoo. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

The back of the same postcard. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

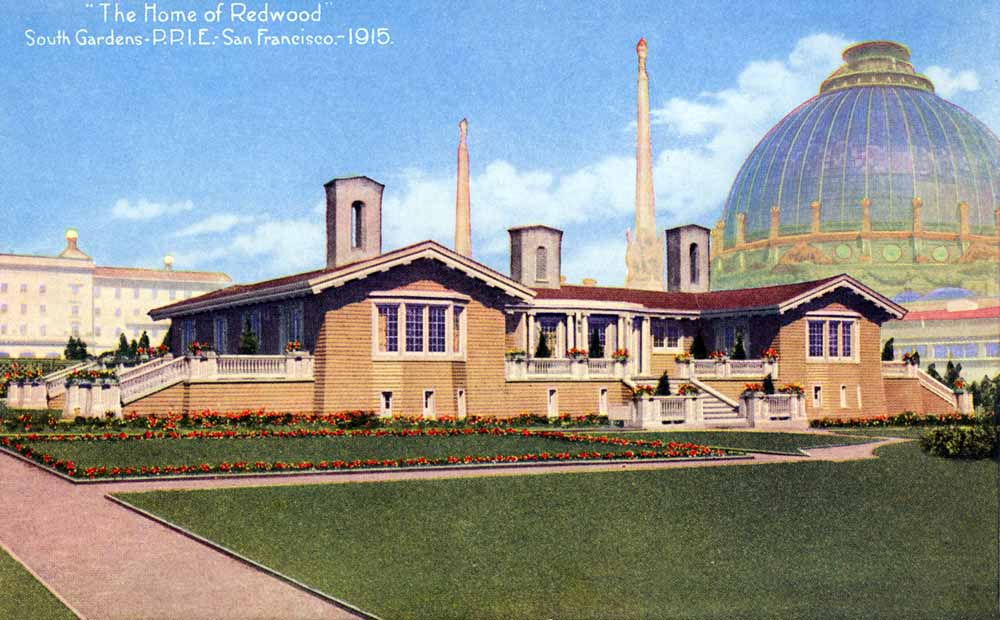

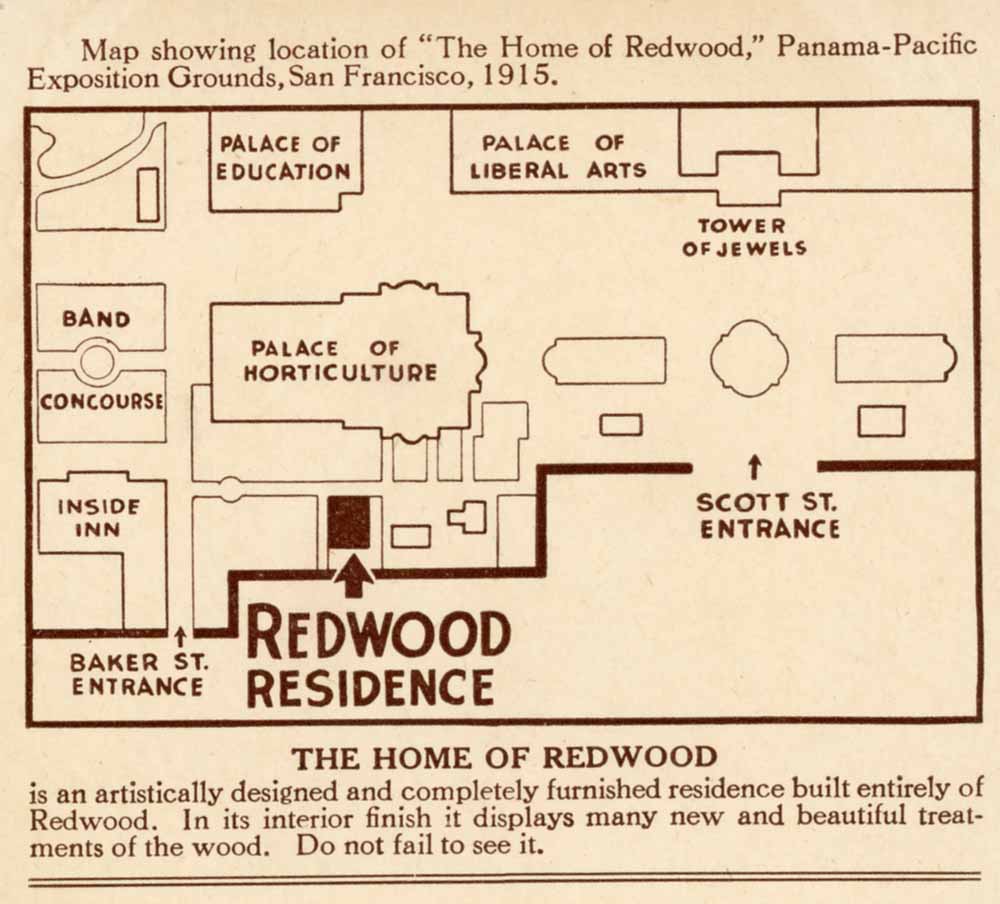

The Redwood Bungalow also got its own postcard. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

The back of the Redwood Bungalow postcard. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

The White & Sugar Pine Industries Building apparently did not rate its own postcard, but this image and the following are from a period issue of Lumber World Review.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

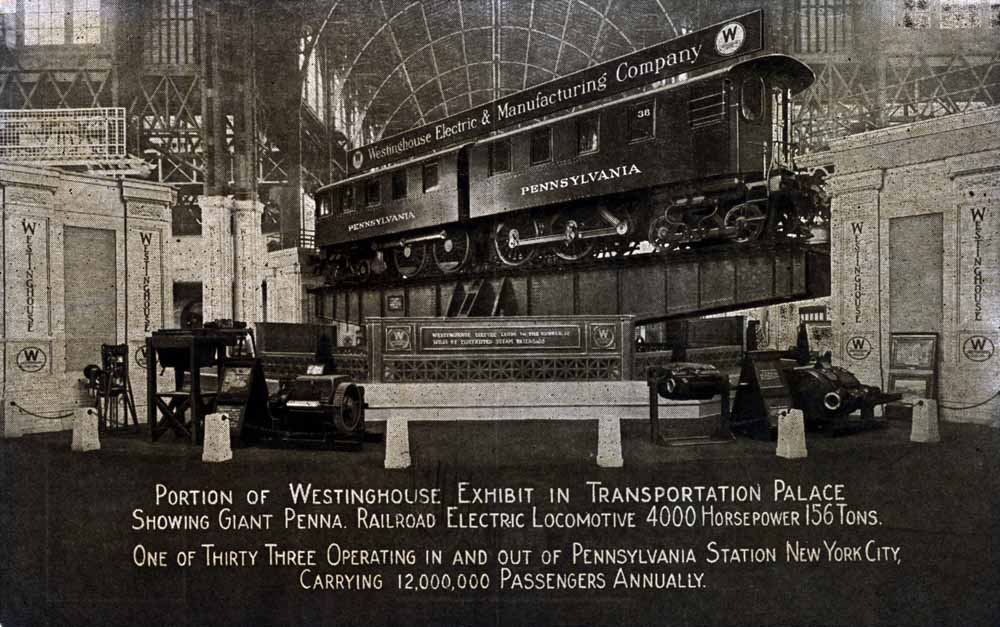

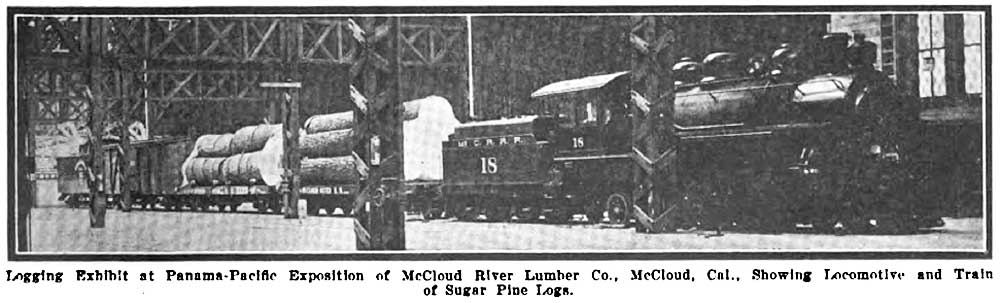

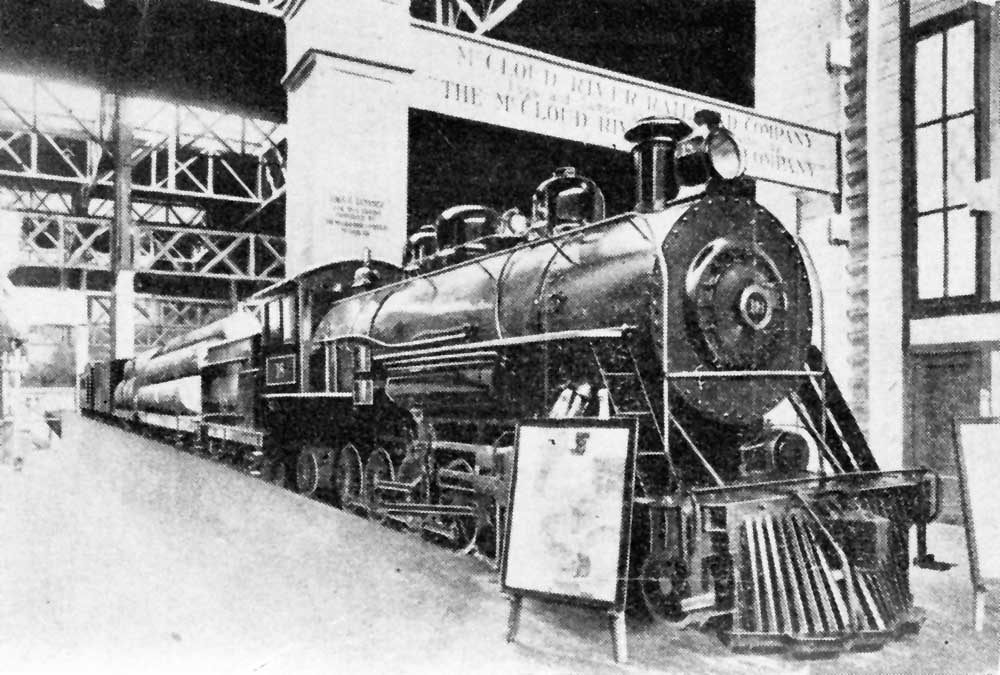

McCloud River Railroad Display Train

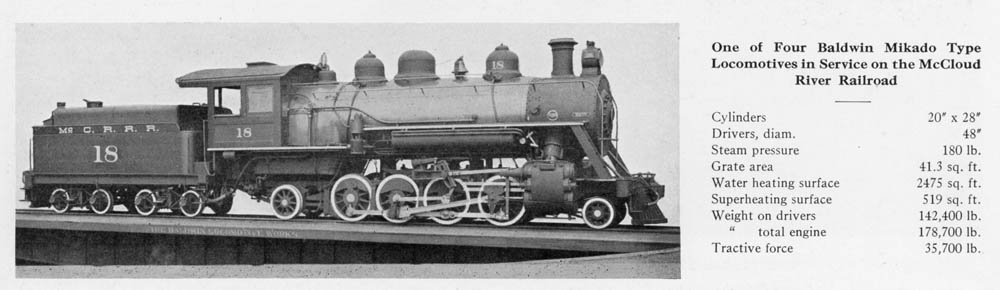

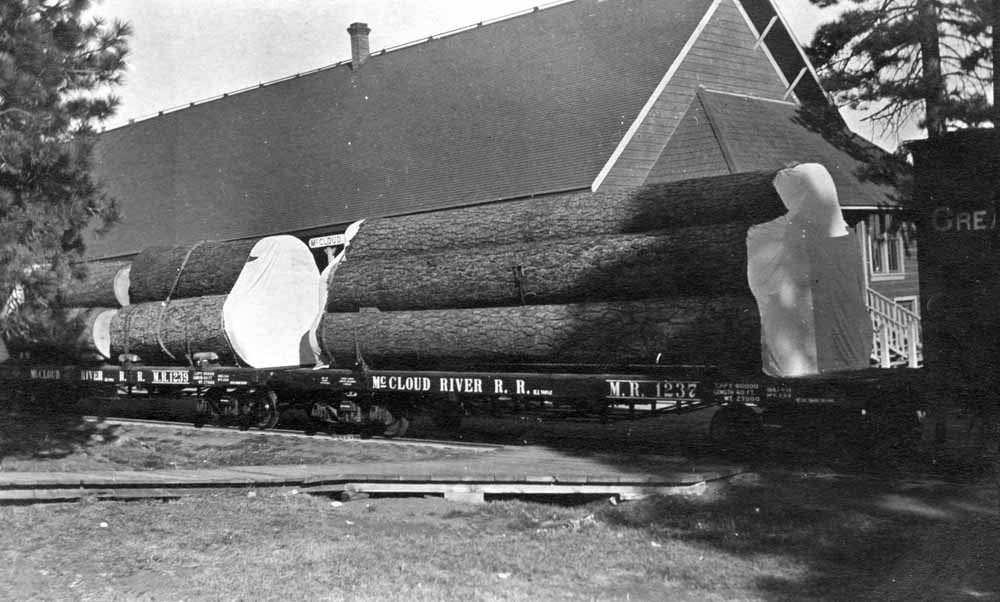

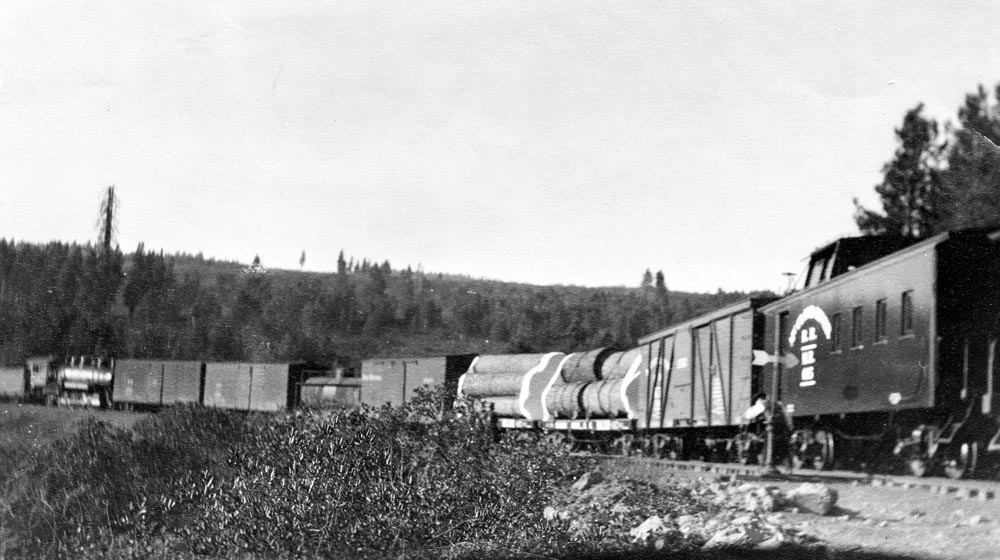

The exposition devoted one of the eight large Pavilions to Transportation, and the McCloud River Railroad assembled a train complementing the White & Sugar Pine Industries Building for display in the Pavilion. McCloud River had effectively decided by this point to purchase another 90-ton Mikado new from Baldwin, and the railroad assumed the order of a machine then in the early stages of construction on the factory floor that had been ordered by an Arkansas logging railroad who had been forced to back out when their financing package fell apart. Baldwin completed the locomotive as McCloud River #18, gave it a special Exposition finish, and shipped it to San Francisco. The McCloud car shop was then in the process of building a series of new 40-foot log flats, and the railroad selected two of them- #1237 and #1239- for display at the Exposition. The company carefully selected and loaded onto the cars sugar pine logs, two sets of 16-foot logs on car #1239 and a set of 32-foot logs on car #1237. The railroad fitted special protective coverings onto the ends of the logs to protect them during the trip to San Francisco. The car shop also built a new side door caboose for display at the Exposition. Finally, the sawmill loaded one of the railroad's new Pullman built boxcars with the finest lumber it could produce. |

|

|

|

|

Builder's photograph of the #18 from Baldwin Magazine.

|

|

|

The #1237 and #1239 with their log loads in front of the McCloud depot. Ray Piltz collection, courtesy Travis Berryman.

|

|

|

Caboose #015 in McCloud just before the display train departed. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

The train preparing to leave McCloud for San Francisco. Heritage Junction Museum.

|

|

|

The display train at Signal Butte on its way to the Southern Pacific interchange. T.E. Glover collection.

|

|

|

The #18 coming from Pennsylvania met the cars shipped from McCloud in San Francisco. The train then spent most of 1915 displayed in the Transportation Pavilion. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|

An entrance to the Transportation Pavilion. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

Some of the exhibits in the Transportation Pavilion. Roger Titus collection.

|

|

|

The McCloud River display train inside the Transportation Pavilion from a period The Timberman.

|

|

|

A drawing of the display train included in pocket calendards the lumber company distributed to customers. The train returned to McCloud in January 1916 after the Exposition closed. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

|