|

McCloud River Railroad 1981-1982 FRA Track Rehabilitation Grant |

|

|

|

|

Jeff Moore collection

|

|

|

|

Introduction

A number of high profile railroad bankruptcies in the later 1960s and early 1970s, but especially the cataclysmic bankruptcy of the Penn Central in 1970, laid bare the multiple problems the railroad industry faced in that era. Decades of underinvestment caused by regulatory strangulation, a significantly overbuilt railroad network in much of the nation but especially in the northeast, and revenue erosion as heavy industries either closed, moved oversees, or shifted to other transportation modes combined to plunge the industry into crisis. The United States Congress responded with a series of Acts passed through the early 1970s designed to stabilize the railroad industry. One of them, the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, contained numerous provisions to aid the railroad industry. Section 5 of the Act in particular appropriated Federal funds for local railroad assistance, to be administered through the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) and state transportation agencies. Under those provisions individual railroads would apply through their states, who would rank and prioritize submitted projects. Each state would then prepare an annual state rail plan recommending the highest ranking projects for funding, after which the states had to prepare formal project applications to the FRA and execute grant agreements with that agency. Projects had to pass a cost/benefit analysis on terms prescribed by the FRA, and the Federal dollars could only cover 80% of the total project costs, with the railroads responsible for funding the other 20%. The significant traffic losses the McCloud River Railroad suffered in 1978 and 1979 called the continued existence of the entire operation into serious question. The railroad's exploration of ways to stay in business led the company to the "4R" Act funding. McCloud's then chief engineer John Dixon P.E. prepared a list of potential track improvements and cost estimates, which the railroad submitted to the California Department of Transportation- Caltrans- on 4 April 1980. Caltrans responded quickly with a letter on 10 April 1980 indicating the railroad's initial application looked favorable for potential funding. That response kicked off a frenzied period of negotiations and conversations through the spring of 1980, during which the McCloud project became one of the top four projects the state decided to carry forward in that year's Railroad Plan. The state held a series of public hearings in August 1980, and the railroad's management directed Dixon to appear at one of them to provide support for the project. John's handwritten notes of the presentation he made on 14 August 1980 at the hearing in San Francisco read as follows. First, I would take this opportunity to thank you, Mr. Chairman, for affording me the opportunity to make a statement during this public hearing. I'm John Dixon, Chief Engineer of the McCloud River Railroad. The railroad, between the Mt. Shasta area and the town of McCloud was originally constructed, with the help of the Chinese, during the spring of 1896, 10 years after the Southern Pacific arrived with railroad at the little town of Strawberry Valley as Mt. Shasta as is known today. The railroad was constructed on a 4-5% grade with many 15 degree reversing curves back to back from Mt. Shasta City, elevation 3550', over Snowman's Summit, elevation 4500', and down into McCloud, elevation 3400'. From the very beginning up until 12 to 14 months ago, the railroad had been a viable entity, envisioned by a hand full of extraordinary men. In 1977 Champion International Corp, our major customer on the Railroad at that time, sold the Railroad to Itel Corp; during the same year the sawmill at Pondosa burned down, eliminating a shipper; Coopers Mill which is located on our line, began in 1977, hauling the preponderance of their primary lumber tonnage by trucks; in 1978 Publishers Lumber Mill in Burney and on our line, was sold to Sierra Pacific Industries and the decision was made by them to shut down the big log mill and cut only small logs which would amount to about 40% of the total board feet that had been cut by the previous owner; in 1979 the Champion International Mill in McCloud was closed down and put up for sale- all of which reduced our average loaded cars hauled per day from 38 in 1976 to 7 in 1980. My review of the Railroad's industry situation points to but one fact: the management of the Railroad had no control over the events with which we are faced with now. As it exists today, the Railroad, from Mt. Shasta to Burney and up to Hambone, is approximately 100 miles long over very steep terrain, which requires long steep grades, high fills, deep cuts, and eye widening sharp curvature. Mother nature continues to be our most resolute opponent in providing a good roadbed for the trains. We have been deferring track maintenance for the past 2 years at a rate of 3 to 4 hundred thousand dollars per year in hopes our business would increase. We do have good prospects of new business at this time thanks to our new president and his staff, that might be forth coming within the next 2 to 4 years. It is, therefore, imperative that the road be maintained at an acceptable FRA Class 2 designation during this interim period, so that we can continue to serve our existing customers safely and on a timely basis. Further, if new business is to be generated for the Railroad it depends mainly on whether we can show on paper how competitive our service is. Your favorable consideration to grant the Railroad 1.3 million dollars will allow this to happen. In closing I'd like to say, that the Railroad has been an integral part of the economy of the North State for a long time and has its roots deep in lumber and steel and it would be a crime to let it all become just a memory. Thank you. |

|

|

|

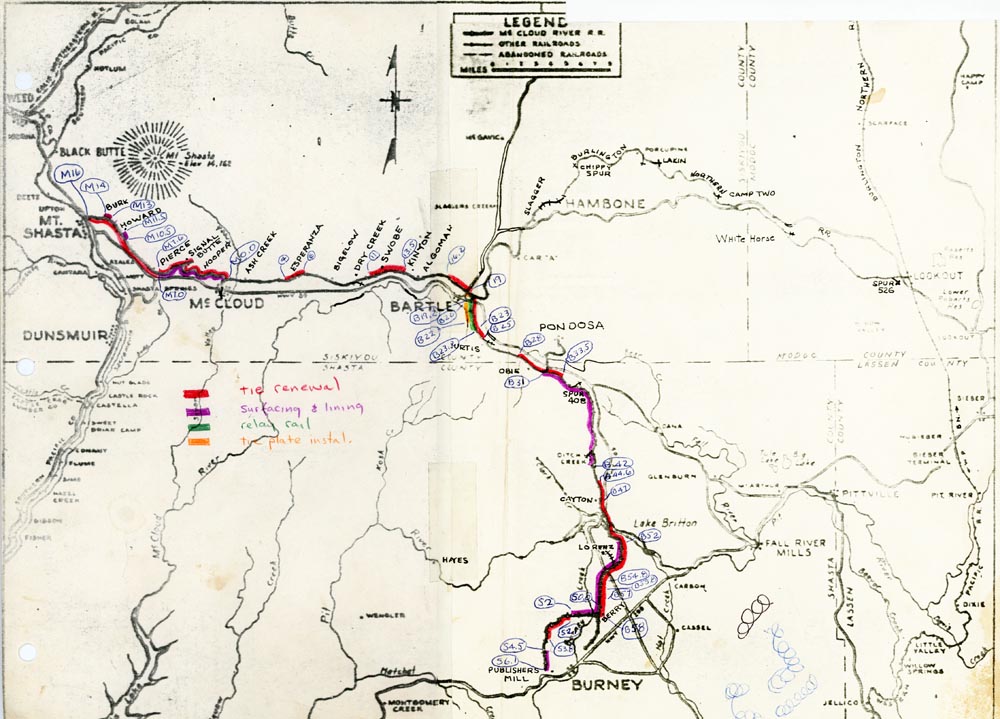

Project Development The initial project list John Dixon assembled contained four basic components, consisting of replacing 20,180 ties, surfacing 30.2 miles of track, relaying 3.3 miles of rail, and installing 29,490 tie plates. The original working total for this work stood at close to the $1.3 million John referenced in his presentation to the public hearing. Allowances for engineering and other incidental costs boosted the total project estimate to $1,571,000. In the late summer of 1980 the railroad hosted several rounds of visits made by Caltrans and FRA officials, most of which included hi-rail tours of the line. The FRA had some questions and doubts about the project, which led to that agency hiring the Thomas K. Dyer Inc. Consulting Engineers firm out of Chicago to perform their own assessment of the railroad and determine project needs. Dyer sent B.J. Kersey, one of their engineers, to McCloud to inspect the railroad on 23 September 1980. Dyer Engineering subsequently produced and submitted to the railroad, the FRA, and Caltrans a report of their findings and recommendations. The full report is available at the following link.

Dyer Engineering Report (Report will open in a new window, close it to return to this page)

September 30, 1980 proved to be a momentous day for the project, as on that day Caltrans published the 1980 California State Rail Plan recommending the project for funding and the FRA issued

their decision officially approving the project. The pages of the State Rail Plan approving the project are available at the following link:

McCloud Portions of 1980 California State Rail Plan (Report will open in a new window, close it to return to this page)

The FRA approval committed $1,280,563 to the McCloud River rehabilitation project, plus an additional $45,000 for engineering and inspection. The FRA in their decision however stated no funds could

be expended on the McCloud River project until the agency had received and approved documents relating to three unresolved issues, as follows: 1. The benefit/cost analysis must be further documented with respect to the estimates used in the analysis. In addition, FRA has some concerns with the benefit/cost methodology that was employed. 2. The State must provide FRA with copies of any proposed contracts. 3. Based on an engineering review of the McCloud River Railroad rehabilitation project, some discrepancies with regard to the quantities of materials necessary for this project have occurred. In addition, the engineers have made recommendations with regard to work not included as part of this project which appears necessary. The State of California should work closely with the FRA to develop quantities that are mutually acceptable. Work on finalizing the project accelerated through the winter of 1980 and into the spring of 1981. By March 1981 Caltrans had a near final project list, though the railroad continued at least suggesting tweaks. Burlington Northern asked some pointed questions as to why McCloud did not include the Bartle to Hambone line in the project, to which the railroad replied it was planning to continue maintaining that line with its own funds, though the real reason likely revolved around BN's then on-going efforts to abandon the Hambone to Lookout line. The project as it stood in March 1981 can be seen in the following letter, along with a few notes on changes suggested by John Dixon:

March 1981 Project Status Letter (Letter will open in a new window, close it to return to this page) |

|

|

|

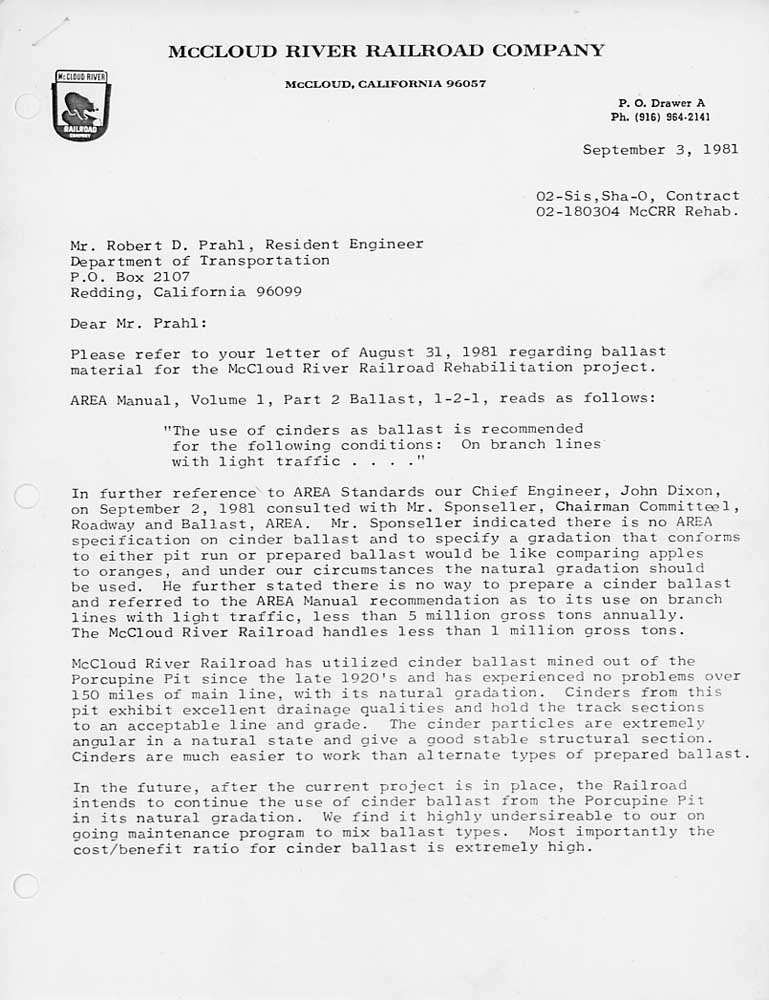

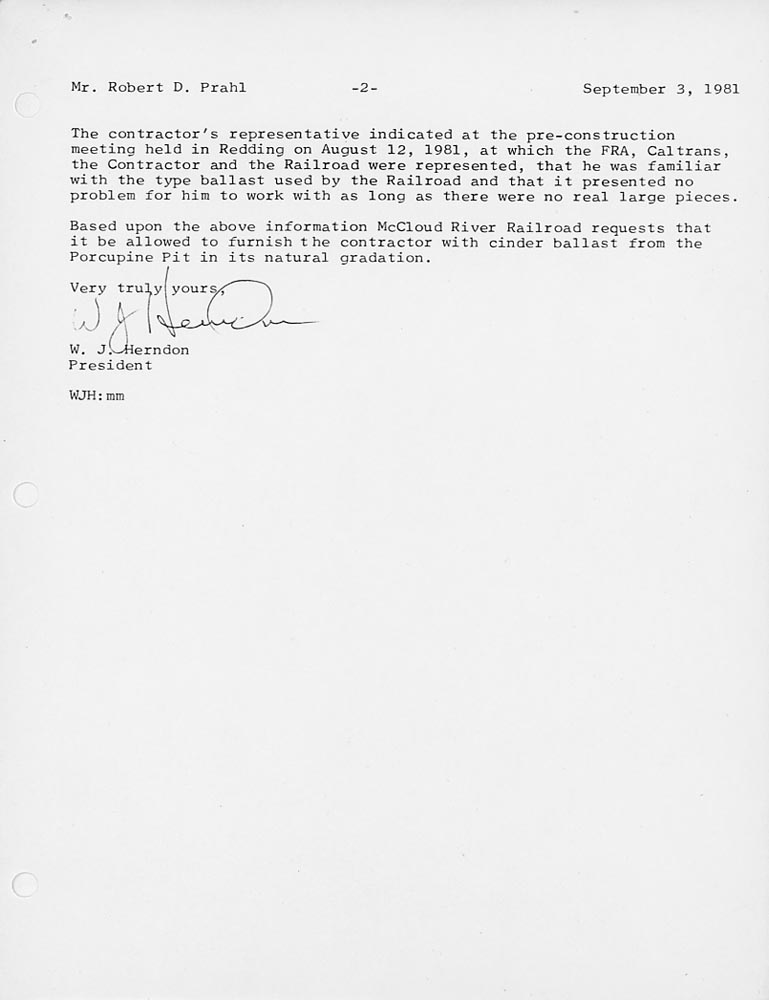

Project Construction Caltrans finally got the project pulled together, with the proposed final plans and specifications provided to the railroad in middle May 1981. After the final adjustments had been made Caltrans advertised the bidding package on 6 July 1981, with all bids due by the 26th of that month. The schedule called for bids to be opened the following day, with the contract to be awarded around 3 August. Southwestern Railway Company of Phoenix, Arizona, submitted the winning bid, and they started work on the project on or around 25 August 1983. Once started work progressed quickly, starting with the tie and rail replacement. Southwest brought in at least one subcontractor, Evans, to do much of the surfacing work. There were several changes to the project, the most significant of which deleted sufacing and lining the track on three segments, specifically the curve between Mileposts 7.8 to 7.9; between Mileposts B-46.2 and B-46.4; and B-45.2 to B-45.5, to be replaced with surfacing, lining and raising at least 1" all of the tangent track between McCloud and Bartle. The project hit one of its biggest snags in early September. During the project preparation period the railroad had agreed to supply all ballast at a cost of $4.50 per cubic yard, to be delivered in quantities of at least 1,000 yards at a time. The railroad hired a contractor, Hammond Brothers Construction DBA Edgewood Enterprises Inc. from Weed, to handle operations at the Porcupine pit, which included quarrying, sorting, and loading into ballast hoppers the 38,000 to 44,000 cubic yards the project would consume. Edgewood brought in a conveyor belt to expedite bringing cinders up out of the pit. Potential problems with using the volcanic cinders from Porcupine first cropped up in late August. On 25 August the Caltrans engineer in charge of the project provided instructions to John Dixon that whatever ballast the railroad provided had to meet American Railway Engineering Association (AREA) standards for things like uniform grading. The railroad provided the following response letter:

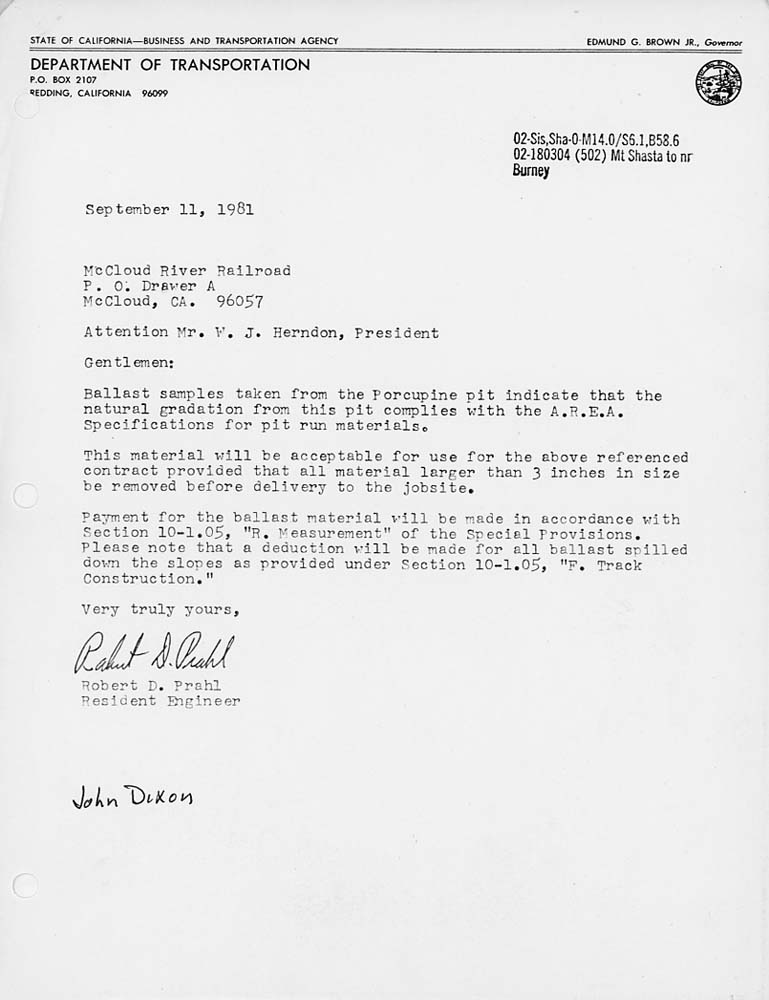

Caltrans responded with another letter on 11 September 1981:

The requirement that the railroad keep all ballast material at 3" or less caused a lot of problems and sparked a meeting held in the railroad offices in McCloud on 11 September. Caltrans wrote a memo documenting the

meeting and the results in a memo dated 14 September 1981:

In the middle of all this Southwest notified the railroad on 4 September 1981 that they would need ballast deliveries to commence in 15 days. The railroad at the time owned six ballast hoppers, two

side dump and four bottom dump, all with a 25-yard capacity, which meant the company could not come anywhere close to delivering the 1,000 yards a day the contract required. The railroad leased at least 21 large hoppers

from Burlington Northern, including two cars each still lettered for predecessors Great Northern and Northern Pacific. Ballast deliveries started on 28 September, but some of these early deliveries included material

larger than the 3 inch maximum size already established, indicating the screening operations at Porcupine had either not yet been set up or fully operational. At its height the railroad was running two dedicated ballast

trains a day shuttling material between Porcupine and the job sites, with between 10-20 carloads of ballast dumped each day. The surfacing work presented its own set of problems, including some allegations Southwest

brought against the railroad for irregular ballast delivery and dumping, and some of the ballast dumping occurred before Southwest could remove all the salvage material rendering it unrecoverable. Southwest for its part

damaged a dozen or so of the railroad's flange oilers along with a large number of gauge bars. Despite the best efforts of everyone involved winter weather arrived before the project could be completed, forcing Southwest to suspend work in early December. Continued snowfall prevented Southwest from returning before late April, which gave the railroad and Caltrans some time to identify and discuss the remaining work, including a number of corrective items. The biggest task completed in May and June 1982 was the two grade crossing replacements. Work on the project wrapped up around middle June 1982. The railroad held a grand dedication ceremony marking the project completion in middle July that drew over 100 people, including various local politicians and dignitaries. The McCloud management and employees at least considered applying again for funds under the 1982 rail plan, with the top considered projects being rebuilding the trestles over Burney and Goose creeks on the Sierra branch and adding a second track at Lorenz to turn the spur into that mill into a wye, but for one reason or another the company apparently did not proceed with the application, probably due to some combination of the state not wanting to fund the same property in back to back years and/or that the railroad may not have been able to come up with the required 20% match. |

|

|

|

Project Legacy In retrospect the track rehabilitation grant proved to be one of the most important occurences on the railroad in the early 1980s time period. One of the constants in the railroad industry is that the physical plant, especially track, requires some minimal level of maintenance every year to stay even with wear and tear and natural deterioration. Deferring work in any one year only doubles the amount of work needed in the next year, and too many years of missed work will easily push any railroad into a death spiral as tracks deteriorate and operations become increasingly slow and unsafe. The McCloud River Railroad had already been deferring track maintenance in the years leading up to the grant, and the work the $1.26 million Federal investment bought not only caught up on the accumulated deferred maintenance, but also preemptively completed a lot of work and improvements the railroad would have needed to do anyway. The grant therefore had the intended short term effect of allowing the railroad to reduce its track maintenance expenditures through some of the darkest years the operation ever faced. This in turned gave the railroad some measure of financial stability, and provided it with a solid base from which to launch the marketing campaigns and other strategies that landed the railroad new customers and increased business in future years. It's not a stretch to say the grant work quite literally held the railroad together for the next three decades, including a lot of years the operation may not have lived to see without the work. On the flip side, the grant work only prolonged what was almost certainly the inevitable end of the railroad, and may have hastened the final demise of the line east of McCloud when it came. One of the rules of thumb in shortline railroad economics in the early to middle 2000s was that in order to remain viable a railroad needed to be spending at least $5,000 per year per mile in track maintenance expenses. The McCloud Railway after operations to Lookout ended stretched 85 miles between the Sierra Pacific Industries sawmill in Burney and the Union Pacific interchange in Mt. Shasta City, and applying that rule indicated the company needed to be spending $425,000 per year on track maintenance. The railroad during the abandonment process lumped track maintenance costs in with locomotive repair and maintenance, work equipment, signal inspection and maintenance, medical and first aid, dues, and subscriptions, licenses and fees, telephone, utilities, legal, travel, office supplies, postage, environmental maintenance, communications, training, shop supplies, and consultation, and to pay for all of these the company reported spending $570,000 in 2002, $588,000 in 2003, and $628,000 in 2004. At no point after 1982 did either the McCloud River Railroad or McCloud Railway generate sufficient revenue to make the kinds of sustained investment in track maintenance needed to stay ahead of deterioration, and one of the repercussions of the grant funding the completion of so much work at one time is that it all reaches the end of its useful life at the same time. The combination of these two factors led to large parts of railroad all starting to fall apart around 2002, which accelerated the end of operations. Below are a series of pictures John Dixon shot in the summer of 1982 of parts of the railroad after the project work had been completed.  The line change at Milepost M-4.5.  A tangent stretch at Milepost M-3.5.  Another tangent section on the 4.5% grade at Milepost M-3.  The long tangent at Milepost 4.  Bartle Wye at Milepost 19.  Evidence of other tie replacement the railroad was doing visible at Milepost B-22.5.  A curve on the fill near Milepost B-24, with some evidence of the uneven ballast dumping visible in the foreground.  Despite not having any further projects submitted, the 1982 version of the California State Rail Plan featured the McCloud River on the cover. Special thanks to John Dixon for providing a lot of the materials and memories on this page and to Lee Hower for scans of the 1980 rail plan. |

|

|